The Green Goddess

by Brian Hawley

|

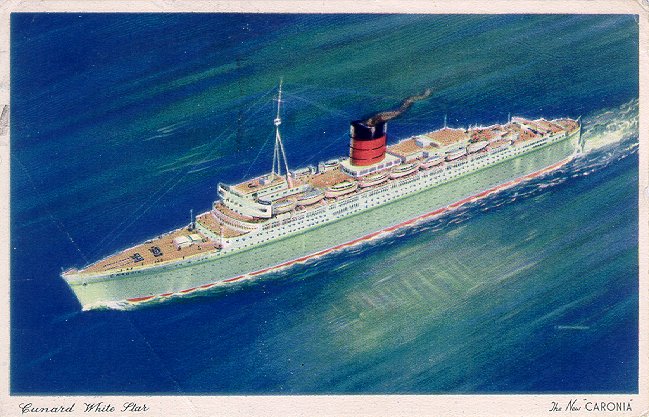

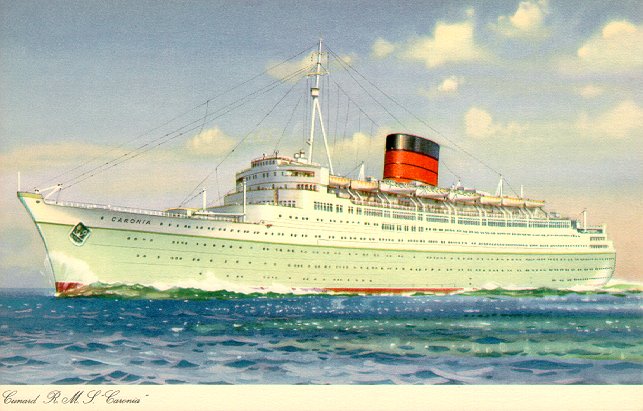

RMS Caronia (II) owes her existence to Cunard Company Chairman Sir Percy Bates. One could make a strong argument that Bates was a genius. Taking the helm at Cunard at the outset of the Depression, his strong hand guided the company through the merger with White Star and the Second World War, and set the stage for the most prosperous period the company had ever known. His unfortunate death in 1946 left a void in the corporation not filled until the 1960s. The last ship Bates would be involved with from inception was the fabulous Caronia. While Caronia was similar in size and speed to the second Mauretania of a decade earlier, Bates made sure that her role for the company would be unique indeed. In the post war period uncertainty was endemic to the shipping industry. Among the concerns Bates would be challenged with were inflation, especially in construction costs. Also problematic were the time consuming task of refitting liners from war duty and the overall state of the highly competitive North Atlantic shipping market. Yet prophetically the Chairman was more anxious about the threat from airliners than many of his successors within the industry. To offer the best value in an uncertain market Caronia was envisioned as a hedged bet. Her size, draft, and speed made her much more versatile compared to the huge Queens. Bates decreed the construction of a vessel with a design that while in many respects a traditional Atlantic liner, Caronia would nevertheless be quite capable as an off-season cruiser. With an eye towards the tropical white paint job of the great prewar globetrotter, Franconia, the new Caronia had her hull uniquely painted in four separate shades of pale green. Ostensibly this paint scheme would help deflect the heat of the sun. In reality this would be the great ship’s trademark and a fantastic marketing scheme, Caronia would thenceforth be known as “The Green Goddess”.

Each year Caronia would follow a similar pattern. January would find her circumnavigating the world or making a loop around Africa. After completing one of these long winter cruises, Caronia would embark on spring voyages to the Mediterranean and Black Sea, with summer spent in Scandinavia and on the Atlantic. Fall in the Caribbean topped off the year. The ship’s cruise passenger-to-crew ratio was amazing, nearly one-to-one. The attention to detail by the staff was legendary. Cunard would fly fresh milk or lobsters to meet the ship in exotic ports. The service was such that several passengers opted to live onboard year round. Mrs. Clara MacBeth for example lived aboard for 15 years, spending $20 million in fares.

Sadly the end came quickly for Caronia. With Cunard’s mounting cash problems in the late 1960s and increasing competition in the cruise market, Caronia was put up for sale in 1967. Purchased by Greek shipping magnate Andrew Kostantinides the ship was renamed Columbia and again Caribia. Hastily refitted, the old Caronia was sent on a couple disastrous cruises out of New York. In March 1969, an engine room explosion at St. Thomas killed one crew member and rendered the ship unseaworthy. She was towed to New York and laid up in Gravesend Bay for five years. The situation was grim. In fact, the city of New York eventually gave the ship a parking ticket. After an auction of her interior goods, Caribia left New York in April 1974, towed by tugs heading for the scrapyards in Taiwan. She developed a small leak while near Honolulu. Towing continued as this was thought to be negligible. Attempting to avoid a tropical storm, the tugs lost control of the old Caronia off the entrance to Guam harbor. The ship ran aground on the rocks near the breakwater, rapidly breaking into three pieces. She was quickly dismantled on the spot. It was a sad ending for Sir Percy Bates’s superb idea.

Brian Hawley maintains a Website dedicated to his two favorite liners: Olympic and Caronia and to Fort Carroll, Baltimore, at http://www.bytenet.net/rmscaronia. |